April 2019

Dave

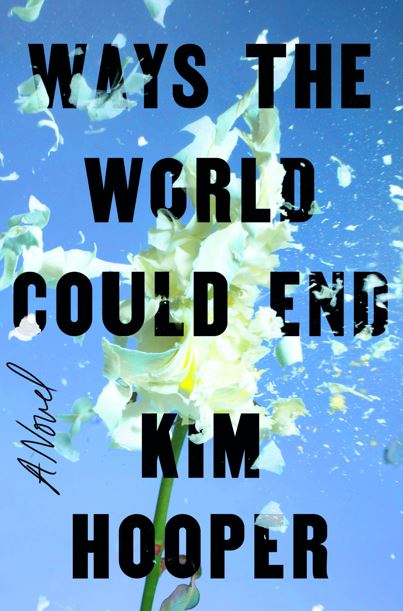

There are several ways the world could end. And it will end. It’s not something that depresses me, which Cleo thinks is weird. I can hear her voice in my head now: Dad, you’re such a weirdo. She says it lovingly—with a laugh instead of an eye roll. I’ve decided this means I’m doing okay as a father.

We’ve had a good run, as a species. Half a million years. We’ve built cities from nothing, created complex languages, visited outer space. We’ve invented and engineered and made the impossible possible. But, as I said, it will end.

Cleo says I’m a pessimist, but I do not agree with this assessment. I am a realist. The fact is that ninety-nine percent of all species that have ever lived have gone extinct, including every one of our hominid ancestors. Our turn will come—sooner rather than later, by my estimation.

The question, of course, is: How?

I believe an asteroid is the most likely culprit of our extinction.

When I was in college, I started reading Neil deGrasse Tyson’s monthly essays in the “Universe” column in Natural History magazine. I’ve been following him ever since—more than twenty years now. He is one of the world’s most renowned astrophysicists, and he’s concerned about asteroids too. He once called them “harbingers of doom.” Theoretical physicist Michio Kaku expressed a similar sentiment: “Sooner or later, we will face a catastrophic threat from space. Of all the possible threats, only a gigantic asteroid hit can destroy the entire planet.”

We’ve come close to catastrophe before. In 1908, a 200-foot-wide comet fragment exploded over the Tunguska region in Siberia, Russia. It had nearly a thousand times the energy of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Astronomers say similar-sized events occur every one to three centuries.

Asteroid impacts are more likely to occur over the ocean, and small ones that happen over land are most likely to affect unpopulated areas (because much of the Earth is water, and much of the land is unpopulated, with humans clustering in relatively few locations). The thing is, with a big asteroid, it doesn’t matter much where it lands. If it’s big enough, it will trigger a devastating chain of events. Asteroids more than a half mile wide strike Earth every 250,000 years or so, and these would cause firestorms followed by global cooling from dust kicked up by the asteroid’s impact. Some humans would survive—and I hope Cleo and I are among them—but the world as we know it would effectively end.

If the asteroid is really big, like five miles wide, there would be no hope for Cleo and me. Humans would be extinct. It would be just like what happened to the dinosaurs.

The greatest asteroid threat seems to be 99942 Apophis. It’s about a quarter-mile wide. This asteroid was formed in the Asteroid Belt in the earliest days of our Solar System more than 4 billion years ago, meaning it has been orbiting the sun all that time. It gradually moved, as many asteroids have, to near the Earth’s orbit millions of years ago. Back in 2004, when it was discovered, early observations suggested a three-percent probability that it could hit Earth on April 13, 2029. Scientists have since ruled out the 2029 possibility, but some are still concerned about 2036 or 2068.

Neil deGrasse Tyson has said that if 99942 Apophis does hit Earth, it will trigger tsunamis and submerge parts of North America. NASA says there is no longer anything to worry about. But I don’t know; I have my doubts. I don’t trust the government to have an adequate asteroid defense plan in place. And I certainly don’t trust them to tell us if we’re really in danger. They don’t want mass hysteria. I have to assume the worst. I have to be prepared—for Cleo’s sake.

______________

“Can you add shampoo to the Costco list?” Cleo says, walking into the kitchen, her hair wet from the shower. The cat follows on her heels, like he does every morning. She is the one who feeds him. Cats are very uncomplicated in their love and loyalty. You would think this would mean I like them, but I cannot forgive them their need of a litter box.

“Sure. Are you completely out, or can you wait until my next trip?”

Cleo knows I only go to Costco one Tuesday a month. I do not enjoy venturing out into the world, so I keep a set schedule of necessary errands. I am a fan of schedules, in general. They give me a sense of control, an “illusion of control,” as Jana used to say. Jana—Cleo’s mother, my wife. She was always encouraging me to step outside my comfort zone, to deviate from my routines, so I tried as much as I could. It was important to her, and she was important to me. But now she’s gone, and it’s just me and my schedules against the world.

Cleo does not share my fears of the outside world, much to my chagrin. If it were up to me, I would home-school her and we would remain confined to a safe and comfortable bubble, just the two of us. But she is fifteen now and reminds me on a daily basis that not everything is up to me anymore.

“Dad, I would die if I had to be with you 24/7.” She said that recently. It didn’t hurt my feelings. Like Ewan McGregor’s character says in that one movie, “The great thing about people with Asperger’s is that it’s very difficult to hurt their feelings.” What was the name of that movie? Jana made me watch it with her. She was always looking for information on my disorder. When I was first diagnosed, years ago now, I’d find stacks of books on her nightstand with titles like “22 Things a Woman Must Know If She Loves a Man with Asperger’s Syndrome” and “Marriage and Lasting Relationships with Asperger’s Syndrome.” I never had any interest in flipping through those books. I didn’t want to know what kinds of things she was finding out about me, what kinds of flaws she was identifying. I hated The Label. I still hate it. Asperger’s. Autism Spectrum Disorder. ASD. When you hear that, you think of an awkward guy who shuffles his feet, stutters, and can’t look you in the eye. That’s not me. I don’t shuffle or stutter. I look people in the eye. “You are high-functioning,” The Therapist told us. She is the one who diagnosed me, the one responsible for The Label. She tried to sell me on it by naming famous people who likely had it—John McCarthy (renowned mathematician and engineer), Henry Cavendish (discoverer of hydrogen), Albert Einstein, Sir Isaac Newton, Bobby Fischer.

“But they were never given The Label,” I told The Therapist.

“Well, autism wasn’t a diagnosis when—”

“So they didn’t know they had anything wrong with them.”

Both she and Jana nodded their concession.

“It’s the knowing that’s the problem,” I said.

Salmon Fishing in the Yemen.

That’s the name of the movie with Ewan McGregor.

“Daaaad. Dad. Earth to Dad.”

Cleo is staring at me with wide eyes that express disbelief at my ability to completely zone out. I get this look a lot.

“What? Sorry.”

She puts dry food in the cat’s dish. The cat is named Apophis, after the asteroid. This was Cleo’s choice (she calls him “Poppy” for short). At first I thought she was showing respect for my interests. She had to explain that it was sarcastic. I’m not great with sarcasm. I’ve been told that this is part of having The Label.

“I said I probably have, like, a week of shampoo left. When is your Costco voyage?”

I look at the calendar I have tacked to the wall next to the fridge. It is where I keep my schedule of all required outings.

“I’m going next week.”

“Well, doesn’t that just work out swimmingly.”

I can’t tell if that’s sarcasm.

She goes to the cabinet for two boxes of cereal—frosted flakes and granola. She likes to mix them, which I find odd, but I don’t comment on it. I know she finds many of my behaviors odd, and she doesn’t comment on them. We have a truce. She pours what I consider to be way too much milk on the cereal, then proceeds to pack her lunch, letting the cereal get soggy because that’s how she likes it, which I also find odd.

She’s made me start buying non-dairy milk—milk made from almonds and oats and coconuts and soybeans. I told her “It’s not milk then; it’s more like juice. Almond juice. Oat juice. You are basically ‘juicing’ these things to create a liquid.” She rolled her eyes and said she didn’t care what I called it, as long as it’s not from udders meant for a baby cow. I fear she will declare herself vegan soon.

“Looks like your worst nightmare is coming true,” Cleo says, standing over the sink, looking out the window. She juts her chin in the direction of something outside.

I go over to her, look over her shoulder.

We live in the hills of San Juan Capistrano, what Cleo describes as “the middle of nowhere.” But that’s just her being a dramatic teenager. It’s not the middle of nowhere. It’s less than fifteen minutes from her high school. It’s just not close to other houses. It’s not in a traditional neighborhood. The land used to belong to a cattle rancher, but he died, and his family sold off his cows and put the property up for sale. So it’s a large, empty pasture with a 1200-square-foot house on it. I don’t have any aspirations of being a rancher. I moved Cleo and me here nine months ago, in summer. I wanted to get away from Before. This is the most away I could get, without Cleo needing to leave her friends and all that. Unlike me, she has those. Friends. I figured she’s been through a lot; as her father, it’s my responsibility to help ensure that she doesn’t have to go through more. The Therapist told Jana and me that people with The Label have trouble with empathy; but I think I’ve cracked that particular nut, at least when it comes to Cleo.

“There’s a moving truck,” Cleo says.

She is pointing to the house two football fields away, a house my realtor had told me had been abandoned long ago. Of course, I did my research: I went to the county office and looked up the deed. The land was owned by a man named Diego de Silva who, as the realtor said, hadn’t lived on the land since 1995—a failed cattle-ranching endeavor, apparently.

“It just looks like a truck. How do you know it’s a moving truck?” I say.

“I guess I don’t know for sure, but there appear to be people transporting things out of that truck and into the house. I believe this is what some people call ‘moving’.”

Sarcasm.

“There’s no way that house is livable.”

Cleo and I had gone over to investigate the house when we first moved in. It was locked up, but we peered through windows. It’s a suitable house, structurally. It’s bigger than ours—two stories. But it’s in complete disrepair—paint peeling off in strips, wood rotted, likely infested with rodents.

“Maybe they’re going to fix it up first,” she says, with a pep to her voice that tells me she’s excited about this development.

“Or maybe they’re coming to tear it down.”

She turns from the sink, her wet hair whipping around and depositing droplets of water on my face.

“Oh, Dad,” she says, with a pat on my back, “always the optimist.”